Measles Q & A

Measles Outbreak: All The Questions You Want Answers To

One in 10 children with measles gets an ear infection, which can lead to permanent deafness.Credit: Francis R Malasig/EPA, via Shutterstock

Via NYTimes, By Pam Belluck and Adeel Hassan

Updated on April 25

The United States is having its worst year for measles since the disease was declared eliminated in the country in 2000. Federal health officials said Wednesday that 695 individual cases have been confirmed in 22 states in 2019.

The growing number reflects the rise of the antivaccination movement in the country and the spread of international outbreaks that have infected American travelers.

New York has been particularly hard hit, with 200 confirmed reported cases in suburban Rockland County, and at least 334 cases in New York City, almost all in Brooklyn. This week, public health officials in Los Angeles declared a measles outbreak in the county, making it the latest metropolitan area to be hit by the illness.

Five cases of measles are being investigated there. California requires childhood immunizations to attend public or private school, with exemptions allowed if a doctor confirms that there is a medical reason to not have all or some shots. It is one of the strictest laws in the country.

Here’s what you need to know about the disease and the risk of getting it.

What is measles?

Measles is an extremely contagious virus. It can cause serious respiratory symptoms, fever and rash. In some cases, especially in babies and young children, the consequences can be severe. Measles killed 110,000 people globally in 2017, mostly children under 5.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in 10 children with measles gets an ear infection, which can lead to permanent deafness. One in 20 children with measles develops pneumonia and one in 1,000 develops encephalitis (brain swelling that can cause brain damage). Pregnant women with measles are at greater risk of having premature or low-birth-weight babies.

One or two in 1,000 children who contract measles will die. In countries where measles vaccination is not routine, it is a significant cause of death, according to the World Health Organization.

How is measles transmitted?

Measles is transmitted by droplets from an infected person’s nose or mouth. If you’re in a room with someone infected with measles, you can inhale their virus when they cough, sneeze or even talk. Infected people can transmit the measles virus starting four days before they develop a rash, so they may be contagious before they realize they have the disease. They remain able to spread the virus for about four days after the rash appears.

The virus can also live on surfaces for several hours, and is so contagious that, according to the C.D.C., “you can catch measles just by being in a room where a person with measles has been, up to two hours after that person is gone.”

What are the symptoms of measles?

According to the Mayo Clinic, people show no symptoms up to two weeks after being infected. Then they develop symptoms typical of a cold or virus: moderate fever, cough, sore throat, runny nose, red and swollen eyes.

But after two or three days of that, fever spikes to 104 or 105 degrees and the telltale red dots appear on the skin, first on the face, then spreading down the body.

Abel Zhang, 1, being helped back into his clothes by his mother, Wenyi Zhang, center, his grandmother, Ding Hong, left, and Dr. Lauren Lawler, after receiving inoculations for measles, mumps and rubella at a clinic in Seattle. Credit: Elaine Thompson/Associated Press

Is there a cure for measles?

No. The vast majority of people who contract measles haven’t been vaccinated, and giving them the measles vaccine within 72 hours of being exposed to the virus might help — at least by reducing the severity and duration of the symptoms. The Mayo Clinic says that pregnant women, babies and people with weak immune systems can receive an injection of antibodies called immune serum globulin within six days of being exposed to measles, which might prevent or lessen the symptoms.

How safe and effective is the measles vaccine?

Extremely safe and effective. The measles-mumps-rubella (M.M.R.) vaccine causes no side effects in most children. Small numbers may get a mild fever, rash, soreness or swelling, the C.D.C. says. Adults or teenagers may feel temporary soreness or stiffness at the injection site. Rarely, the vaccine might cause a high fever that could lead to a seizure, according to the C.D.C. Contrary to misinformation that some anti-vaccine activists continue to repeat, the vaccine does not cause autism.

Children should receive two doses of the vaccine: the first when they are 12 to 15 months old; the second when they are between 4 and 6 years old. If infants who are between 6 and 11 months old are about to travel from the United States to another country, the C.D.C. recommends they receive one dose of the vaccine beforehand.

One dose of the vaccine is about 93 percent effective; two doses boost that number to 97 percent, the C.D.C. says.

People who don’t get the vaccine are at very high risk for contracting measles. “Almost everyone who has not had the MMR shot will get measles if they are exposed to the measles virus,” the C.D.C. says.

If I’m not vaccinated, is it too late to get the shot?

It’s not too late. In fact, if measles is occurring in your community, it’s a good idea to get vaccinated unless you are sure you have previously received two shots of the M.M.R. vaccine; or you’ve had all three of the diseases the vaccine protects against (which gives you lifelong immunity); or you were born before 1957. (The vaccine was made available in 1963 and in the decade before that, virtually every child got measles by age 15, so the C.D.C. considers people born before 1957 likely to have had measles as children.)

But people who received the vaccine in the 1960s should consider getting immunized again. One of two vaccines available from 1963-67 was ineffective, the C.D.C. says. The effective vaccine during those years was the “live” vaccine; the ineffective one was the inactivated or “killed” vaccine. If you’re not sure, consult with your doctor.

If most people are getting vaccinated, why does it matter if I don’t vaccinate my child?

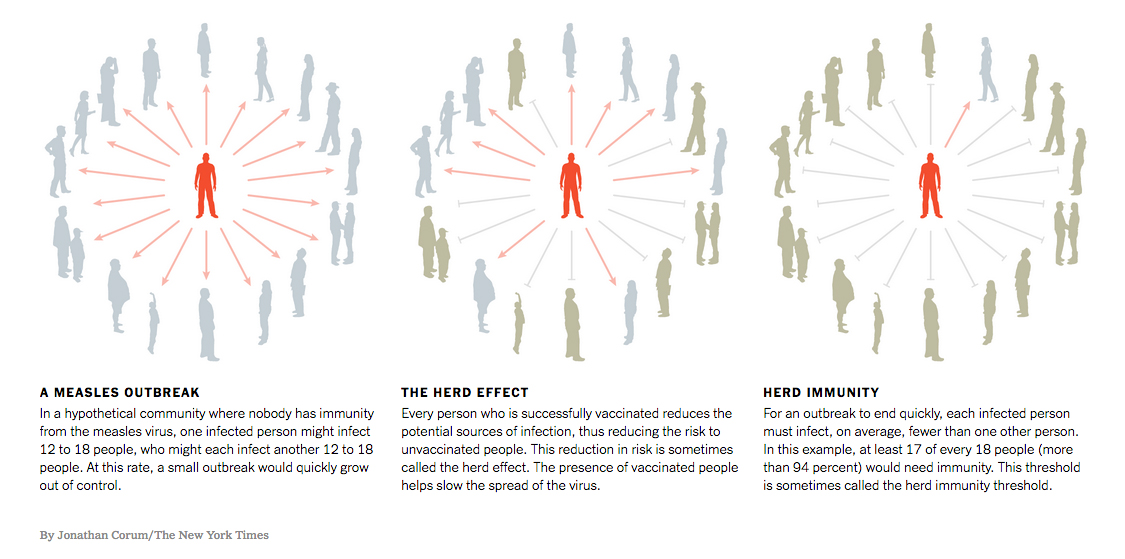

You are probably thinking of the concept of herd immunity, which means that if a large number of people are protected from a disease by a vaccine, the disease will be less likely to circulate, diminishing the risk for people who are unvaccinated. The threshold for herd immunity varies by disease — for a highly contagious disease, a very high percentage of people need to be vaccinated to meet that threshold.

Because measles is so contagious, between 93 percent and 95 percent of people in a community need to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Remember, some people can’t be vaccinated for medical reasons: infants, pregnant women and people who are immune compromised.

During the Disneyland outbreak in 2015, a 9-month-old child whose parents were planning to immunize contracted measles from an older child who hadn’t been vaccinated, said Dr. Annabelle De St. Maurice, an expert on infectious diseases at U.C.L.A. So vaccinating your child not only protects your child, it helps protect others in your community.

Wait, didn’t we eliminate measles?

In 2000, measles was declared eliminated from the United States because the country had gone for more than 12 months without any “continuous disease transmission” within its borders. “Eliminated” doesn’t mean the disease was completely eradicated; it means the United States no longer had any places where the disease was endemic or homegrown.

There have been a small number of measles cases in the United States since then, ranging from 37 in 2004 to 667 in 2014, largely among people who were not vaccinated.

Most of the American cases since 2000 have been the result of people traveling to or from countries where measles is endemic because there is little vaccination.

How many people haven’t been vaccinated?

A small number in scattered pockets. Measles immunization in the United States is stable and high — more than 90 percent — according to C.D.C. tracking.

Who are the people not getting vaccinated?

One way to measure is by looking at the annual assessment of kindergarten vaccinations. It shows only Colorado, the District of Columbia, Idaho and Kansas dipping below the national 90 percent vaccination rate, though in certain communities the rate can be lower.

Generally, those who do not immunize their children are demographically more white and more educated, Dr. De St. Maurice said. “In part due to the success of vaccines, people are not as familiar with these diseases, so they question their effectiveness,” she said. Conversely, when the disease reappears, as it did in Washington, demand for vaccines rises.

Don’t states have laws requiring parents to vaccinate their children?

Every state has these laws. Three states allow only medical exemptions: Mississippi, West Virginia and, more recently, California, following the Disneyland outbreak. The rest grant exemptions for personal, philosophical or religious beliefs as well.

Are the states with lax laws the ones with the most measles cases?

There have not been enough cases to warrant a major survey, but Dr. Saad Omer of the Emory Vaccine Center in Atlanta warned that with a rising number of cases, that could change.

Dr. Omer, who studies immunization coverage and disease incidence, said research had shown that states that allow more exemptions have increased pertussis (whooping cough) outbreaks.

Studies have also shown that people who refuse vaccines are disproportionately represented in the early stage of outbreaks. “They’re providing the tinder that can start the fires of the epidemics,” Dr. Omer said.

How does the U.S. compare with other countries?

Measles cases have been increasing around the world, too. Worldwide, there was an 80 percent drop in measles deaths from 2000 through 2017. But reported cases of measles have increased 30 percent since 2016, according to the World Health Organization.

Ninety-four percent of children in the United States get the recommended two-dose vaccine. According to the World Health Organization, more than a dozen countries reached the 99 percent mark, including Cuba, China, Morocco and Uzbekistan. Canada, Britain and Switzerland are a few of the Western countries that are below 90 percent.

In Europe overall, only about 90 percent of children receive the recommended two-dose vaccine. Worldwide, about 85 percent of children receive the first dose, but the number drops to 67 percent for a second dose, data shows.

Does this mean mumps and rubella cases are re-emerging, too?

The M.M.R. vaccine has also greatly reduced the threat of mumps and rubella in the United States. It is not quite as effective against mumps, with 88 percent effectiveness, according to the C.D.C., and cases have increased in recent years, from 229 in 2012 to 6,366 in 2016.

Rubella used to cause millions of infections in the United States. According to the C.D.C., 12.5 million people got rubella in an epidemic from 1964 to 1965, and the disease caused 11,000 women to lose their pregnancies, 2,100 newborns to die and 20,000 babies to be born with congenital rubella syndrome, which can cause brain damage and other serious problems.

Rubella was declared eliminated in the United States in 2004, and the C.D.C. says that fewer than 10 cases are reported each year. But, as with measles and mumps, there are still many countries where it persists because of lack of vaccination, and every case since 2012 has been traced to people infected while traveling or living in another country.

Pam Belluck is a health and science writer. She was one of seven Times staffers awarded the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting for coverage of the Ebola epidemic. She is the author of “Island Practice,” about a colorful and contrarian doctor on Nantucket.