Even Nobodies Have Fans Now

Nick Walters listens to a bunch of different podcasts, but none speak to him the way “Failing Upwards” does. The weekly show, hosted by the men’s-wear enthusiasts and self-proclaimed “grown dirtbags” Lawrence Schlossman and James Harris, undertakes to navigate the “millennial male zeitgeist.” Mostly, they talk about clothes and New York.

Walters, a 24-year-old commercial banker, lives in Cleveland. He first heard about the show from a friend and recognized himself not just in the hosts but also in its community of listeners — mainly guys on Instagram who share his perspective on fashion and life. “If I know that another guy listens to ‘Failing Upwards,’ we’re going to talk about it,” he says. “It’s kind of like a TV show, like if you’re into ‘Game of Thrones.’ ”

Much like “Game of Thrones,” “Failing Upwards” claims its own extended universe. Fans are known to one another as the Fail Gang. They worship the same streetwear god (Jonah Hill) and a sartorial ritual known as “the fit check,” hypebeast-speak for “Who are you wearing?” Walters fantasizes about going on the show and already knows what he would wear: a pair of Yeezy Boost 700 Wave Runners, a John Elliott hoodie and Eric Emanuel basketball shorts. He likes these clothes, but just as important, he believes that this outfit would impress Schlossman and Harris. “I want to meet the hosts so bad,” he admits. “I want to be friends with them.” He plans on moving to New York someday, and he told me that if they cross paths, he believes that could happen. “We have enough similar interests and a similar sense of humor that, yeah, I think we would hit it off.”

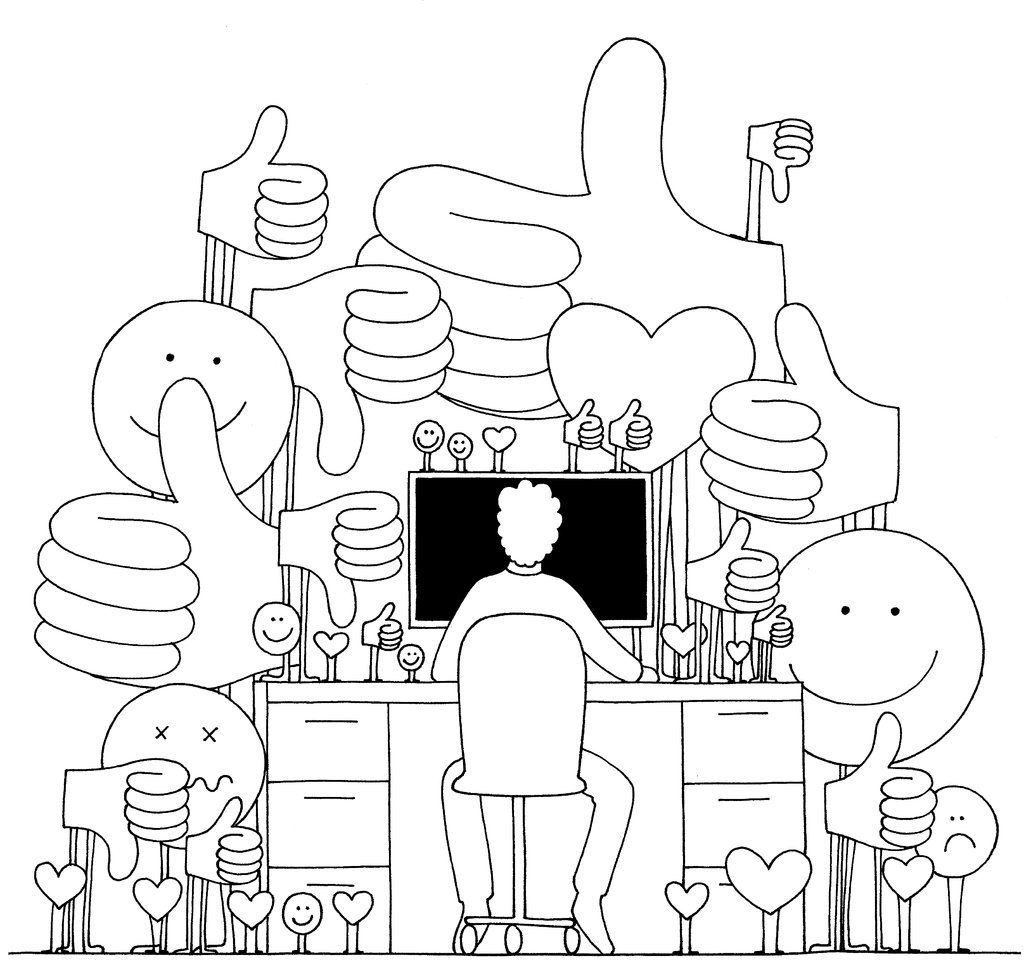

All across the podcast realm, from the heights of self-help to the depths of true crime, imagined relationships are blossoming. Listeners may press play for the content, but many of them eventually come to nurture something like a one-way friendship with the hosts. This kind of daydreaming is an in-joke of the form, best articulated by a popular meme: On first glance, it appears to be a picture of a kid eating ice cream with his friends. Upon closer inspection, he’s actually alone; the three laughing women are models printed on a billboard advertising ice cream. The caption: “How it feels to listen to podcasts.”

Among sociologists and armchair theorizers, this unique type of pining is known as a parasocial relationship — a term coined in 1956 to describe the connection between television viewers and a new class of entertainment personalities, including announcers, game-show hosts and anyone else who spoke in direct address to the camera. “The spectacular fact about such personae is that they can claim and achieve an intimacy with what are literally crowds of strangers,” the sociologists Richard Wohl and Donald Horton wrote in Psychiatry. “This intimacy, even if it is an imitation and a shadow of what is ordinarily meant by that word, is extremely influential with, and satisfying for, the great numbers who willingly receive it and share in it.”

Parasocial relationships are, by definition, one-sided, but like normal friendships, they can deepen over time, enriched by the frequent and dependable appearance of the charming persona on the television set. Podcasts, with their own unique set of formal quirks, are perhaps even better poised to foment this kind of bond. An ideal complement to multitasking, the podcast is ingrained in daily household chores, the morning commute, the bedtime routine. A two-way conversation can be taxing. Podcasts allow us to get to know someone else without all the stress of making ourselves known. If listening demands anything at all, it’s only a bit of imagination. As hosts chatter on, we might picture their faces, their posture, their clothes, the empty cans of seltzer on the table, perhaps even their off-air lives beyond the show. “The host is this disembodied voice that is pervading your intimate spaces, so there’s kind of that room for imaginative bonding between the listener,” says Gina Delvac, producer of the friendship podcast “Call Your Girlfriend,” hosted by Ann Friedman and Aminatou Sow. “You have to remember that there’s no fourth wall. When you’re talking to someone, you’re whispering in their ear. You’re in the shower with them. You’re on their commute to work.”

Over hours of listening, the asymmetry increases. Hosts begin to feel like dear friends, while listeners remain eternal strangers. For the hosts themselves, and other figures who exist within the extended universe of a show, the lopsidedness can feel awkward or uncanny. When Delvac — a silent but known character in the “Call Your Girlfriend” universe — meets fans on the street, she’s often consumed by a feeling of amnesia. “They’re like: ‘Oh, my God. We know each other. We know each other so well!’ And I’m like, ‘Did we go to school together?’ Was she, like, my sister’s friend? ‘How do I know you?’ I’m, like, racking my brain,” she explains. “It can seriously feel sometimes, from the producer or podcaster end, like having a brain injury or some weird sci-fi disease.”

This sense of connection to a distant stranger begins, unsurprisingly, with religion. Fanaticus, the Latin origin of “fan,” was used to describe female temple attendants driven into frenzy by devotion to the gods. This type of chaotic piousness, as a secular behavior, might be traced to the mid-1800s, a time when mass culture was on the rise. In a recent New Yorker article, “Superfans: A Love Story,” the writer Michael Schulman finds early examples in the concert-hall frenzy known as Lisztomania and the protests in England that followed the fictional death of Sherlock Holmes. The shortened word “fan” first appeared around 1900 in reference to the enthusiastic crowds at baseball games. Throughout the 20th century, the term would grow in scope to include worshipers of any entertainment figure — from matinee idols to Elvis to the Beatles. At that point, such devotion was a personal affliction, enjoyed alone in an adolescent daydream. Though fans might write letters, attend concerts or join clubs, the ability to band together as a group was still somewhat limited by the bounds of time and space.

Our modern sense of “fandom” — not just 50 million Elvis fans, but a community of 50 million Elvis fans — most likely began with the Star Trek conventions of the 1970s, which helped create a new infrastructure for fan engagement. These early gatherings of a few thousand people in a rented hotel ballroom would eventually give rise to phenomena like ComicCon, enormous gatherings that have reconceived fans not just as passive viewers but as active, and highly integral, participants. They are no longer merely worshipers of a top-down product but creators and stewards of a shared, bottom-up identity.

Today’s fandom is more like a stateless nation, formed around a shared viewing heritage but perpetuated through the imaginations and interrelations of those who enjoy and defend it. When their common cause comes under threat — through chart competition, cancellation or critique — fans can organize to increase streams, denigrate critics and rally executives to right perceived wrongs. Often they even resort to using the tools of politics while seeking redress. After this year’s disappointing “Game of Thrones” finale, more than 1.7 million fans signed a Change.org petition to remake Season 8 with “competent writers.” (So far, no change has been made.)

In an age defined by political dysfunction, the appeal of any sort of democratically secured victory — however small, however pathetic — isn’t hard to understand. Now that the fandom template has been cemented, it has begun to attach to more obscure or arcane media enterprises: indie-pop artists like Charli XCX, faceless meme makers and even podcasts. The profit model of the podcast world is arranged, perhaps serendipitously, to capitalize on this type of fan relationship. Justin Lapidus, vice president of growth marketing and digital products for the direct-to-consumer linen brand Brooklinen, says podcast listeners are a perfect match for the company’s core demographic: 18-to-54-year-olds with “higher household incomes.” When he looks for shows to advertise on, he tends to make “efficient” plays for smaller, but more committed, audiences. “It doesn’t really matter what genre their podcast is in,” he says. “Whatever they buy, their listeners will buy, for the most part.”

Beyond advertising, podcasts that achieve solvency tend to do so through a stitched-together network of social-media hustles, the sum of which serves to cultivate and monetize an audience’s sense of connection. Though large podcasts often enjoy financial support from traditional media companies and emergent podcast networks, many small and midsize shows — arguably those most indicative of the form — have come to rely on Patreon, a membership platform that invites fans to become financial supporters of creative projects in exchange for a tiered benefits package of the creator’s invention. At the lowest membership tiers, usually $1 to $5 per month, podcast supporters receive benefits like bonus episodes or access to V.I.P. chat rooms. As the tiers increase in price, the rewards grow more substantial, often involving direct engagement with the hosts or entry into the universe of the show itself.

Beyond advertising, podcasts that achieve solvency tend to do so through a stitched-together network of social-media hustles, the sum of which serves to cultivate and monetize an audience’s sense of connection. Though large podcasts often enjoy financial support from traditional media companies and emergent podcast networks, many small and midsize shows — arguably those most indicative of the form — have come to rely on Patreon, a membership platform that invites fans to become financial supporters of creative projects in exchange for a tiered benefits package of the creator’s invention. At the lowest membership tiers, usually $1 to $5 per month, podcast supporters receive benefits like bonus episodes or access to V.I.P. chat rooms. As the tiers increase in price, the rewards grow more substantial, often involving direct engagement with the hosts or entry into the universe of the show itself.

Through these high-tier benefits, the parasocial bond can take on a degree of two-sidedness, absorbing qualities of conventional friendship, but only in a partial, commoditized way. For $51 per month, the hosts of “Dumb People Town,” a comic “celebration of dumb people doing dumb things,” will visit your social-media profile, then film themselves reacting to your life in the same way they break down stories on the show. For $100 per month, the host of “McMansion Hell” will make fun of “a building of your choice”; the hosts of “Mueller, She Wrote” will invite you on the podcast to “share your fantasy indictment league picks.”

According to Wyatt Jenkins, senior vice president for product at Patreon, podcasts are the second-largest category on the site, and the fastest-growing. In the past three years, the number of Patreon pages for podcasts has quadrupled, while revenue intake in the category has increased eightfold. “Roughly 40 percent of our members — this is a guess — are probably doing it altruistically,” he says. “As a vertical, podcasting communities retain memberships very, very well. A lot higher than some other verticals. They release regular weekly content, and they create this incredibly strong bond.”

Because both Patreon pages and ads depend on a sense of personal connection, podcast hosts benefit further when an audience corrals itself into something like a community. This most often occurs in Facebook groups, Discord servers or subreddits — online forums that transform isolated passive listeners into active participants. Some podcast tribes even claim their own names: There are the naddpoles (“Naddpod”) and the MBMBAMbinos (“My Brother, My Brother and Me”). There’s the Scoop Troop (“Hollywood Handbook”), the Wholigans (“Who? Weekly”) and Baby Nation (“The Baby-sitters Club Club”). Fans of “Pod Save America” can be recognized by their T-shirts, which proudly proclaim “Friend of the Pod.”

When these online communities are especially successful, they tend to spin off into subsidiary forums. The wildly popular true-crime podcast “My Favorite Murder” supports a vast constellation of unofficial Facebook groups, many only tenuously connected to the subject of the show. Listeners, who self-describe as Murderinos, can now join “My Favorite Curls” (for murder fans with curly hair), “My Favorite Murder Disnerderinos” (for fans who love murder and Disney), “My Favorite Skin Condition” (for Murderinos with eczema and psoriasis) and “My Favorite Free Emotional Labor” (for calling out and educating problematic Murderinos). In one metagroup, called “My Favorite Thunderdome,” members can tag Murderinos from other subgroups and sub-subgroups for the sole purpose of arguing. This group puts out a regular roundup, “The Weekly Thunder,” which summarizes drama from elsewhere in the “My Favorite Murder” Facebook universe. Once you’re this many layers deep, the podcast itself becomes something of an afterthought — just one moving part in the more complex Murderino ecosystem. “Some of them are people who are, like, too into murder,” says Sophia Carter-Kahn, a frequent lurker in the group who listens to the show only occasionally. “I’ve seen people who are like, ‘I bought this tooth online that’s from this, like, murder victim.’ ”

At the furthest end of this fandom paradigm, the community itself is large enough to begin to overtake the very podcast it came from. The subreddit forum for the left-wing comedy podcast “Chapo Trap House” is, at least in name, a forum for discussing the weekly show. In practice, it serves as an erratic clearinghouse for whatever content its fans feel moved to post: socialist memes, cringe-worthy right-wing tweets and, very often, objections to the show itself. Even among fans, such critiques are numerous, prone to rebuking the show’s overwhelming whiteness, its inconsistently calibrated irony and its outsize reputation on the left. (The show takes in about $142,000 per month on Patreon.) Critiques of the show itself are so frequent that they’ve now become a kind of meme on the subreddit.

In one semi-sarcastic post calling for a “Chapo General Strike,” fans joked that they would cancel their subscriptions unless the show met certain demands: a single nonwhite guest, equity for the producer Chris Wade, the host Felix Biederman’s naming four women he likes who aren’t in his immediate family. Among the more serious, and more ubiquitous, demands was a call for the show to cancel, denounce or otherwise divorce itself from the host Amber A’Lee Frost, who regularly transgresses the discursive norms of the online left. (Frost most recently drew flak for giving a flippant interview to the British website Spiked, which ran under the headline “Meet the Anti-Woke Left.”)

Frost, for her part, has called the show’s subreddit an “incubator of smug, joyless, antisocial sanctimony,” which raises the question: What, exactly, are its members really fans of? If a podcast is not its particular content, and the certain set of people who choose to make that content, then what exactly is a podcast at all?

A few years ago you might have said podcasting was just radio for the internet. Today, the audio is almost beside the point. Today’s podcast hosts are not just on-air personae, but community managers, designers of incentives, spokespeople for subscription toothbrushes and business-to-business software. The worth of a podcast is no longer just its content, but rather the sum of the relations it produces — fan to host, fan to fan, fake friends eating ice cream on billboards together.

Jamie Lauren Keiles is a writer who lives in Ridgewood, Queens. She last wrote about Mike Gravel’s presidential campaign.

Illustrations by Mrzyk & Moriceau. Photo illustration by Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari