by Michael Bailey | Jun 1, 2020 | Health & Medicine, Psychology, Society and Culture |

Connecticut is but one single solitary state that has clamped down on public activity, business operations, and asserted itself in cautious messaging to its residents for the last two months.

There are 49 other states in our country. Many have done the same, if not more. Some have done less. Still other state governments, in doing little from the start, or acting late, have cemented their reputation as lands of questionable judgment.

I am fortunate to live in a community with a leading educational institution that publishes articles such as these to remind readers to stay vigilant, and stay smart. But, there’s more to it than that. People can not wait for articles like this to magically drop from the sky into their lap. We need to proactively follow writers and dispensers of information that are interested in our public health and knowledge scores. Not politics and commerce interests. I “choose” to subscribe to, and trust, posts and information lines like these.

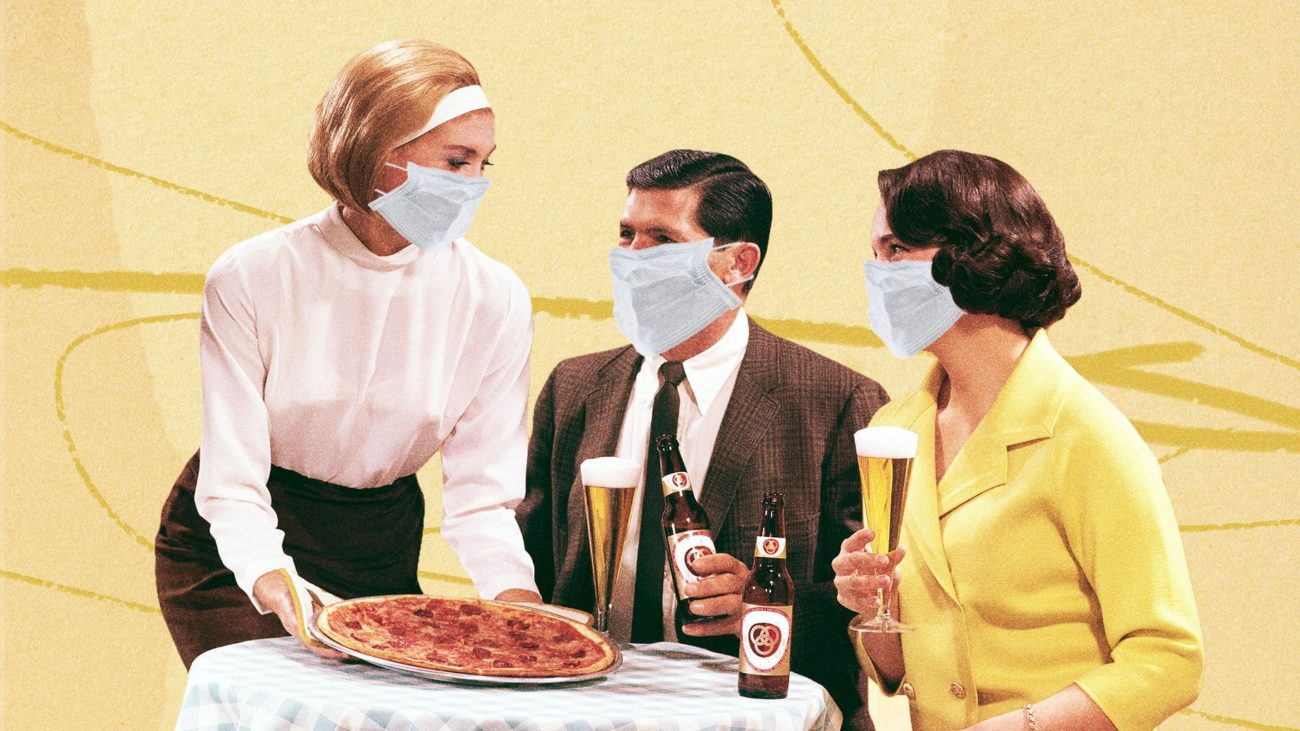

As I drove through a couple neighboring towns in New Haven this past “re-opening” week, I noticed some things that changed literally overnight. Restaurants have set up outdoor tables wherever they can in hailing distance of wait staff. At one of these outdoor table, sat four diners kicking back in their summer shorts, golf shirts, and sleeveless dresses, crowing, laughing, having a good ol time while throwing back beers as if all were finally as it should be. I couldn’t help thinking this group, as many others, felt it should’ve been this way all along since early April. Just down the road, at a popular tequila bar, sitting at a single hi-top table positioned directly on the sidewalk, just aside of its main entrance, and inarguably, encroaching on foot traffic passing by, sat five people elbow to elbow indulging in happy hour. Over the next days more of these sightings were obvious. People sitting together in parties of four, or five, just barely six feet apart from more tables with other people having food and drinks brought out to them. In virtually all of these scenarios, the tables were directly on the sidewalk, sometimes, not always, separated by a waist high iron or wooden fence, where pedestrians were walking by close enough to pick a french fry off a table.

I know I’ve got company who would find both these scenes unsettling at this time and place. I also know there are others who are next in line to grab a table and damn the torpedoes. Thus is the pervasive contradiction of human behavior which opposes as much as it embraces, sometimes with careful deliberation, sometimes with thoughtless impulse.

Ever since this viral mess reached its second month in April, no less June, there’s been as much discussion about the social casualty of isolation, as there has been about the economic and health casualties. There have been so many stress points trying to reconcile these very different vested interests, that the conversation inevitably degrades into conflict, judgment, and lost tempers among people who might not otherwise be colliding in their lives.

The question was glaringly obvious. How is it possible to prioritize these three distinct focal points affecting human beings in such direct and powerful ways, each of which has its own intertwined impact on the other? To me, it is almost impossible. Where does impossible leave us?

It became clear to me months ago, and remains so, that these challenging times are at the top of the list of what organized central government was conceived to address. For instance, conceiving and executing comprehensive plans to address major issues impacting our economy, our public health, and our societal well being. Sadly, during this time, it also became clear, that our federal government would fail us spectacularly in this fundamental mission.

So, are we back to impossible after all? I don’t believe it is impossible IF reality is faced, sacrifices are made, and the inevitable losses are accepted. If we as individuals, as groups, as calm, meditative thinkers, with respect for ourselves, and life around us, gather credible information about this public health risk, and act responsibly, we can salvage the best outcome for ourselves. Even given inevitable losses, there’s a control for a better or worse outcome. Its horrible. Its been horrible. People died. More will die. Business closed. More will close. People lost jobs. More will lose jobs. Still, I ask, you want better, or worse?

Covid -19 is still here. It still gets people sick, and it still kills. As true as it was in February and March, it is true now. Any single action by any given individual in the public space has the potential to trigger a transmission contact, and that person to the next, and so on, and so forth. In case any of you have lost sight of this. This is how an epidemic, and pandemic works. It’s how we got here in the first place. It’s not just about what one person does, or one small group of tipsy teenagers throwing back shots at a crooked table outside a dive bar. It still is about all of us. Its still the same. The virus is still here in plain sight. And there’s still no cure for it.

Let’s all just say for the millionth time. It sucks. It sucks thinking about this all the time. But, we still have to think about it. We still have to think twice before we decide to act like we used to act.. So let’s do that. Think twice.

>MB

Reprinted from Yale School of Public Health: Link>

“Risk of Resurgence” in COVID-19 Epidemic if Connecticut Reopens Too Quickly, YSPH Report Finds

As Connecticut tentatively reopens this week after a two-month shutdown, a new report by the Yale School of Public Health warns that if people resume normal activities and contacts too quickly there will be a “sharp resurgence” in hospitalizations and deaths in the coming months.

Associate Professor Forrest Crawford and postdocs Olga Morozova and Zehang (Richard) Li created a mathematical model to predict COVID-19 transmission, hospitalization and deaths in the state under “slow” and “fast” reopening scenarios.

If the state reopens too quickly, a second wave may be unleashed, the effects of which could be worse than what has already happened. It could result in an estimated total of over 8,100 deaths by September 1 in Connecticut. More than 3,500 state residents have already died from coronavirus.

“If contact rates return quickly to levels seen in early March, the number of new cases could rise dramatically over the summer” said Crawford, the report’s lead author. “Connecticut decision-makers need to closely monitor data on new cases and hospitalizations, as well as transmission model projections, in order to reopen the state safely.”

Under a slow reopening scenario (defined as relaxing restrictions so that contact increases at a rate of 10 percent each month) the incidence of the disease will still increase slightly in the coming weeks but will taper off and stay at lower levels. Hospitalizations for the disease will continue to decline, rising slightly in August and the number of coronavirus-related deaths will rise slowly, with an estimated total of 4,600 to 7,100 by September 1.

Under the fast scenario (defined as increasing contact at a rate of 10 percent every two weeks), Crawford and colleagues found that the number of new infections is likely to spike throughout the summer, potentially exceeding hospitalization capacity and resulting in anywhere from 5,400 to 13,400 total deaths by September 1.

“These projections are based on the latest available data and knowledge from the scientific community,” said Li. “As we gather new evidence about transmissibility of the disease and effectiveness of interventions, our model projections will improve.”

If contact rates return quickly to levels seen in early March, the number of new cases could rise dramatically over the summer.

The researchers attributed the recent decline in hospitalizations to the reduction in contacts following distancing measures implemented by the state officials. “It is too early to return to normal. As some businesses reopen, it is even more important for people to continue practicing social distancing and avoid traveling to highly affected areas, most importantly New York City,” said Morozova.

Yale School of Public Health Professor Albert Ko co-chaired Gov. Ned Lamont’s ReOpen Connecticut Advisory Group, which strongly advised a cautious and conservative schedule as the state starts to return to normal.

“These model projections of the future risk of COVID-19 resurgence directly informed the recommendations made to mitigate this risk,” Ko said. The advisory group, which recently completed its work, was not involved in the preparation of the report.

Other key points from the report include:

- Real-time metrics (such as hospitalizations, case counts and deaths) may not provide adequate warning to avoid a resurgence.

- Closure of schools and the state’s stay-at-home order greatly reduced transmission of the virus.

- There are substantial gaps in knowledge about critical aspects of the disease, including the proportion of infected individuals who are asymptomatic, infectiousness of children, the effects of testing and contact tracing on isolation of infected individuals and how contact patterns may change following reopening.

Reprinted from Yale School of Public Health: Link>

Access full report: Link>

by Michael Bailey | May 22, 2020 | Health & Medicine, Society and Culture |

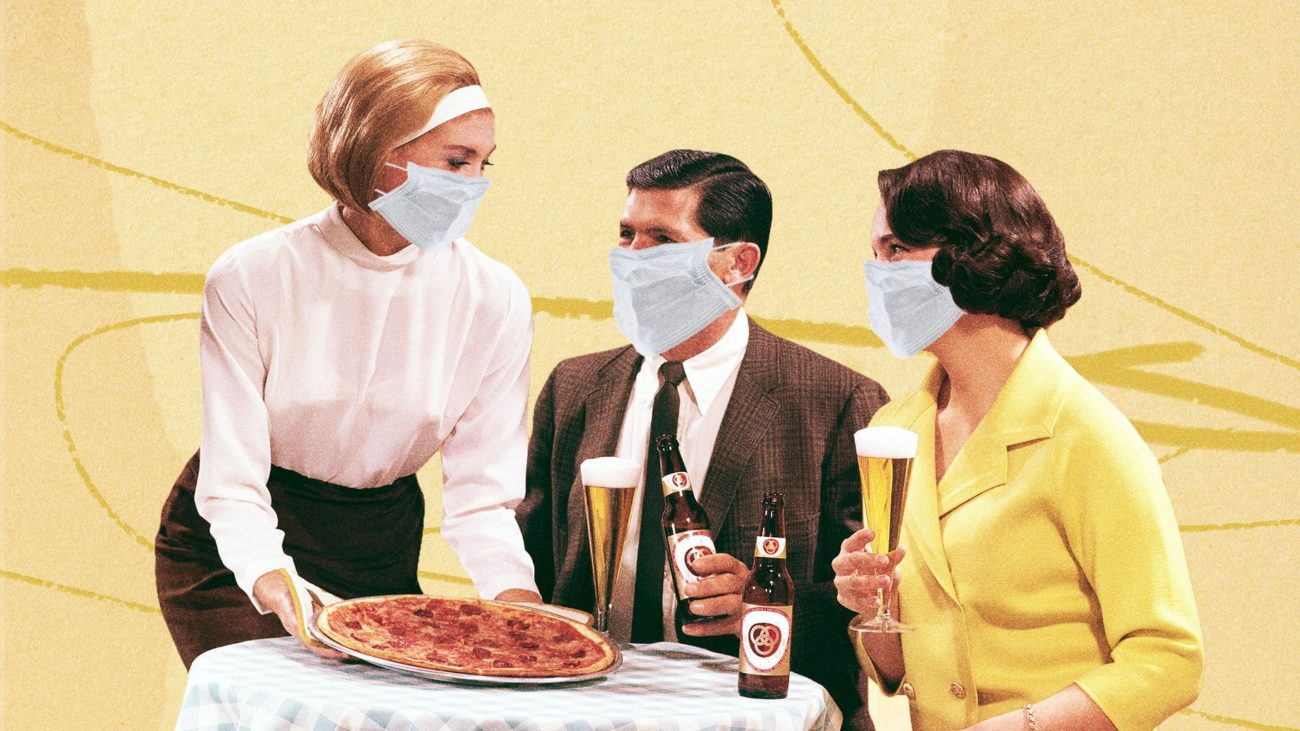

As I’ve written previously, the decision on how we as individuals react to official reopening announcements should be taken in a serious context first, and foremost, within actual virus transmission rates, and testing volume, and ongoing testing access. I’ve said it before. I will say it again. This virus is still a significant threat to public health, with virtually all the same risk factors that were there from the beginning. What’s changing now is not the virus risk, but the way specific businesses are going to operate within the risk environment. Whether you as an individual feel safe enough with those changes to re-enter these environments, just because there is a legal allowance of sorts, is a question you’ll have to answer in your private deliberation. Don’t expect it to be easy. Personally, I’m with the 72%. -MB

The Country Is Reopening—Now What?

Yale Medicine expert answers commonly asked COVID-19 questions as states begin to reopen.

For many, news that the country is reopening during the COVID-19 pandemic is met with a sense of anxiety and confusion.

Reprinted from Yale Medicine

By Joseph Piccirillo, May 20, 2020

Summer is coming. Usually, the season comes with thoughts of beach days, ice cream, baseball, and day camp. But for many, the prospect of summer during the COVID-19 pandemic is met with an overall sense of anxiety and confusion—and questions.

Is the beach safe? The ice cream shop is open, but should I really go? And more importantly, how are we any better off, in terms of infection prevention and treatment, than we were in mid-March, when stay-at-home orders were first put into place?

In other words, why are we reopening now, and how do we make sense of it all?

“I think it is hard for all of us to wrap our heads around reopening,” says Jaimie Meyer, MD, MS, a Yale Medicine infectious disease specialist. “There is nothing magically ‘safe’ about May 20, and very little difference in epidemiologic risk between May 19 and May 21. Only a public health approach that is data-driven will dictate a slow and measured reopening.”

Reopening criteria confusion

Part of the confusion may lie in the number and scope of documents detailing the suggested criteria required for reopening the country. The White House has a protocol called “Opening Up America Again,” the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has its own version, in addition to six one-page infographics, and some states, including Connecticut, have their own plans, some of which are more or less stringent than the White House’s protocol.

The idea, in theory, is that once the state-specific version of the reopening criteria has been met, it will be safe to begin what’s called a “phased reopening”—in other words, a gradual relaxing of some restrictions, as well as the opening of some businesses. With a phased reopening, state officials (working with county and local officials) are presumably able to monitor the number of COVID-19 cases, and can move forward with—or stop, if need be—further reopenings, or phases, based on changes in those case numbers.

But many states have opted to overlook federal criteria—or create their own smaller-scale benchmarks—and move forward with a phased reopening anyway, leaving it up to individuals to make their own decisions about when and how to venture outside safely.

Most Americans are worried about this. According to a recent Reuters national poll, 72% of adults in the United States said people should stay at home “until the doctors and public health officials say it is safe.”

With that in mind, we spoke with Dr. Meyer, who provided answers to frequently asked questions about COVID-19, especially as it relates to the reopening of the country.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. Why is it important to have a consensus on the criteria for reopening?

A. The purpose of having standards for a phased reopening is to ensure that the response is data-driven. I strongly believe that if criteria are not met, we risk an uptick in new cases and a setback in terms of progress with this disease.

Q. What does a data-driven public health approach to reopening look like?

A. Five things, really. 1) The presence of protective immunity. There are a number of people (depending on where you live) who have now been infected with SARS-CoV-2, recovered, and have potentially developed antibodies against the virus. Although it’s not clear yet whether these antibodies will completely protect them from reinfection, at what level and for how long, there is likely some protective immunity; 2) The ability for hospitals to care for patients. As hospitals reduce their overload, they will have expanded capacity to care for people who become sick; 3) Adequate testing. Testing is expanding (or should be) in most states, increasing the potential to identify people who are sick and isolate them; 4) Contact tracing. This is also scaling up (or should be) in most states, increasing the potential to identify even more people who are infected and isolate them; and 5) Careful restrictions on social distancing, cleaning and disinfecting, and PPE [personal protective equipment] in public spaces, all of which reduce the spread of disease.

We need all of these components together to keep the curve going down and to prevent a second wave.

Q. Before a safe and effective vaccine is developed, is the goal to make the virus disappear or to let people get infected, but at slower rates that hospitals can keep pace with?

A. The goal of the combined public health measures I just mentioned is to reduce the number of new cases which, in turn, reduces the number of hospitalizations and the number of COVID-related deaths. No one can expect that these measures will “disappear” the virus, or that everyone will eventually become infected. The truth will likely lie somewhere in between, but only the data will tell us exactly where.

Q. How can we be sure that testing is accurate across all states?

A. It’s hard to know. There are a wide variety of types of tests being used across health systems, and they have varying degrees of sensitivity—meaning the ability to pick up ‘true positives’ for people who actually have the disease—and specificity, which is the ability to tease out ‘true negatives’ for those who do not have the disease.

Tests generally fall into three major categories: tests that look for the genetic material [RNA] of the virus; “antigen” tests that look for a particular part of the virus; and “antibody” tests that look for the human body’s response to the virus.

Some of these tests have been fully vetted and validated before they were approved by the FDA [Food and Drug Administration], and others were authorized under an emergency use authorization [EUA] but have not yet been fully vetted and validated. We are really learning on the fly.

Q. Why is there still a delay in the number of tests being made available?

A. This relates to the capacity to collect the samples, availability of materials to run the tests (nasal swabs or liquid reagents to process the samples, for example), and certified labs to analyze the tests.

Q. The FDA issued two EUAs for at-home tests, one for a nasal swab sample and, more recently, one for a saliva sample. Does that mean we will be able to pick these up at a drug store for routine testing?

A. Yes, home collection kits are likely headed our way. This is exciting because it will not only make the tests more widely available, but also reduce risks of exposure to health care workers that can happen during the collection process. But, I believe home collection kits will still need to be ordered by a health care provider instead of being available over the counter.

Q. What is contact tracing? If I am contacted, does that mean I have the virus?

A. Contact tracing is a way to identify those who have been exposed to people with confirmed cases of COVID so they can get tested—it’s a key component of disease containment strategies. Departments of Public Health everywhere, including in Connecticut, are ramping up their ability to conduct contact tracing. They already have systems in place for other highly communicable diseases, such as syphilis, so I imagine it will operate in a similar way.

If you are contacted, it means you had a potentially high-risk exposure to someone who was infected with COVID. This is not a reason to panic, but rather a reason to self-isolate and get tested.

Q. For how long will we have to wear masks?

A. We may have to have some sort of barrier protection for our faces, like cloth face coverings, until we have highly effective vaccines available.

Q. So, it could be for a while—years, even.

A. Yes.

Q. How does wearing a surgical mask or a cloth mask protect others if small particles carrying the virus can still get through?

A. I like to think of facial coverings as putting your thumb over a hose—some water may escape, but the major flow is blocked. Facial coverings like cloth masks prevent many particles from being disseminated into the environment, but not all. That is why we need social distancing and other prevention strategies, like hand washing and cleaning or disinfection, in addition to cloth masks.

Q. The six-foot physical distance is based on previous coronaviruses, correct? Is it enough? If I am around runners or people who are coughing a lot, should I move farther away?

A. Yes, that’s true. If people are coughing, sneezing, or breathing heavily they may aerosolize more droplets, which may be propelled further. That is why we ask people who are sick to stay home, wear facial coverings, and remain socially distant.

Q. If you’re running for a long distance behind someone, though, wouldn’t that increase your risk? Is it better to move across the street?

A. There is no data on whether it is better to run behind, in front of, or to the side of someone while running. The best bet is to run at least six feet apart, regardless of the direction.

Q. There was a study in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) about SARS-CoV-2 being in aerosols and remaining in the air for three hours. Is that the same as airborne transmission?

A. This means that once virus-coated droplets are sprayed into the air, they can remain there and survive for up to three hours. This facilitates airborne transmission of the virus from person to person, because that live virus can infect someone else if it enters their respiratory tract.

Q. Wouldn’t that mean that we are all susceptible to potential infection in any enclosed space, even if we all wear cloth face coverings?

A. We have to be careful when we translate lab experiments into real-life scenarios. The experiment discussed above found that live virus could be recovered from aerosol for up to three hours, but it’s not known whether the quantity is enough to actually cause infection in someone else.

As the state/country reopens, however, we know that better-ventilated spaces result in less distribution of the virus-laden droplets. This is the reason for states recommending reopening of outdoor spaces first, where transmission is less likely, especially with social distancing.

Q. That means that two families who are on separate blankets six feet apart at the beach would be relatively safe, even if they stayed on their blankets for 8 hours or so, breathing in the same air.

A. Yes.

Q. Some people think they’ve already had COVID-19 in December or January. Is there a way for people to know if they had it? And if they did, do they have some immunity?

A. People who have COVID-19 (whether or not they were ever officially diagnosed) and recover often develop antibodies against the virus. Antibody tests have been developed but are problematic because of high rates of false negatives and false positives. So, right now it’s not recommended that they be used to make individual decisions about personal health or safety. We suspect that antibodies will offer some protection from reinfection, but it’s not known what level of antibodies is sufficient and how long that protection will last.

So, we don’t want people going out to get tested for antibodies and then feeling falsely assured that they are protected.

Q. When returning from the grocery store, is it really a smart strategy to wipe down packaged food with bleach wipes, or is it overkill? If a delivery driver with COVID sneezed on or near my cardboard Amazon package and then dropped it off on my doorstep and I picked it up immediately and opened the box, could I get sick?

A. I think we need to balance anxiety with practicality and safety. I suggest that people practice reasonable precautions. This means unpacking groceries/deliveries from their containers or boxes, washing hands, and wiping down countertops with bleach. Even though the virus can be found on cardboard for up to 72 hours, the NEJM article suggests viable [live] virus is probably on cardboard for closer to 8 hours. Your best bet is to wash your hands after handling potentially contaminated surfaces.

Q. Do we know how long someone is contagious when they’re asymptomatic?

A. People can shed virus (and potentially infect others) for three to five days prior to developing symptoms. Those who don’t develop symptoms at all can shed virus for approximately 14 days at high enough levels that they may be contagious to others.

People can shed virus for weeks following recovery, but we think that this is either dead virus or virus at low enough levels that they are not contagious to others.

Q. In Connecticut, gatherings of 5 or fewer are OK, and most people have been sheltering-in-place for about two months. So, is it safe for one person to have an indoor visit with someone else if both have sheltered-in-placed for two months and have not had any symptoms for 14 days?

A. Data from over 1,000 people hospitalized in a single week in New York showed that the majority of people infected and newly admitted were people who identified as “mostly staying home.” The likely reason for this discrepancy was that there were gaps in home isolation behaviors—social visits with others, being in public spaces without face coverings or appropriate hand hygiene, interacting with others without taking precautions, etc. I know many people who would say they are fully isolated, but are still spending time in public spaces. So, if both people were truly isolated, it would be reasonable to have a visit without any additional risk. Ideally, people could get tested before they gather together.

Q. Some have missed a mammogram or a colonoscopy or a dental procedure, and they’re afraid to go to the doctor. Is there a safe way to get these things done?

A. Over the next few months at Yale New Haven Hospital, we are looking towards reopening ambulatory services and elective procedures, as are places elsewhere that are on the downside of their COVID curve. I think telehealth will be with us for the foreseeable future at least to some extent. In the earliest phases of reopening, in-person care will likely be prioritized for urgent health concerns. But please don’t miss your routine vaccines and health screenings as we move forward in reopening. General preventive healthcare remains important for long-term and overall health.

Q. What do you think needs to happen before you’re confident that we can get this under control?

A. Expanded testing and contact tracing. Safe and effective vaccines. Effective treatment. All are on the horizon and scientists globally are working at a breakneck pace to make these a reality.

Q. Anything you want people to know as we start to reopen around the country?

A. People who have underlying health conditions that place them at higher risk of severe COVID-19 will need to practice precautions for the foreseeable future. I know everyone has COVID fatigue. We have message burnout, are tired of being home, and mourn our “regular” lives. But reopening must be paced and careful and responsive to data so that we don’t backtrack.

Unsure about a COVID-related term? Click here to read Yale’s COVID-19 glossary.

Learn more about Yale’s research efforts and response to COVID-19.

by Michael Bailey | Jan 29, 2020 | Government & Law, Politics, Psychology, Society and Culture |

Some people want to be the king. Their personality patterns suggest the future.

Bill Eddy LCSW, JD, Via Psychology Today

“Presidents are not kings,” wrote Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson on Monday, in requiring a White House lawyer to testify in response to a congressional subpoena.1

Last month, The Nation reported about British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson: “The allure of supreme personal power has always been strong for Johnson. As a child, he told a family friend that it was his ambition to be ‘world king.’”2

An oped in the Wall Street Journal last month was titled, “Putin Is the New King of Syria.”3 Not too long ago, a book was published called The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin.4 Similar books and articles are being written about at least a dozen other world leaders.

Is there a “Wannabe King” personality? Did all of these leaders want to be a king since childhood? If so, what is their personality pattern of behavior? Can we predict some of their tendencies for the coming year?

I believe we can. The following is based on the research I did on a dozen world leaders for the book Why We Elect Narcissists and Sociopaths—And How We Can Stop!

Fantasies of Unlimited Power

Wannabe Kings appear to have one and only one goal: unlimited personal power. This is one of the traits in the DSM-5 for Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD).5 It is not an unusual characteristic, as many people in families, communities, and at work will recognize it.

Yet as world leaders, they appear to take it to an unusual extreme. They co-opt a political party—on the far left or far right—and give the appearance of having like-minded policy agendas in order to gain followers on their road to power.

Yet they have no loyalty to party or policy. When they get into power, their policies are based on what will gain them more power and their whims along the way to demonstrate how powerful they are.

In 2020, expect seemingly inconsistent, unpredictable, and at times whimsical policies, yet each of which is designed to ultimately give the Wannabe King more power.

Targets of Blame

In order to gain power, Wannabe Kings are preoccupied with blaming others—their targets of blame or fantasy villains. They consciously select these targets based on several characteristics, including that the targeted individual or group is somewhat familiar but relatively few in number, and politically weak, yet alleged to be secretly powerful.

Historically, examples of fantasy villains were Jews (Hitler), Kulak peasants (Stalin), and Communists in the federal government (McCarthy), to name a few. In modern times, they have been drug addicts (Duterte in The Philippines); gay people (Putin); journalists (Erdogan, Trump); and immigrants (Orban, Johnson, Trump, and several others)—even though immigrants are the weakest group, with no political power and little wealth.

In 2020, expect Wannabe Kings to increase their blaming of old and new targets in speeches, tweets, and Facebook posts that sound realistic and masquerade as political issues to be endlessly debated. Yet as we have learned about all high-conflict people, “The issue’s not the issue—the personality is the issue.”

Taking Over Legislative and Judicial Power

Wannabe Kings try to take over the functions of the legislature and the judiciary, so they can rule without restraint. Maduro of Venezuela replaced the National Assembly with his own legislature, filled with loyalists, who were empowered to re-write the constitution. Orban of Hungary forced the retirement of senior supreme court justices (who were opposed to his power grabs) to make way for his own appointees. Putin took over most of the power to fire governors and appoint legislators in his first few years in office. Boris Johnson suspended parliament this year, although the British Supreme Court overruled him. And Donald Trump has worked to sweep in a one-party judiciary, with hundreds of conservative judges appointed who are more likely tolerate the expansion of presidential power.

Wannabe Kings will not stop after unsuccessful power grabs. but will try one political issue after another. When they win, they gain power, and when they lose, they quickly announce a victory and move on to the next pursuit.

Fantasy Crises

All Wannabe Kings claim there is a terrible crisis that needs a heroic leader to fight against an evil villain. This is how they gain wide public support: fear of this villain. This is a typical con artist maneuver of distraction; the crisis tends to be a fantasy that they pump up with dramatic, highly exaggerated, or non-existent details.

Hitler used the Reichstag Fire (a small, non-threatening fire) to claim a crisis that convinced the parliament to give up all their power to him. Stalin used a grain crisis (which he primarily caused) to help him force peasants off of farms to collectivize the Ukraine and Russia. Putin said there was a crisis of politicians who were pedophiles, which he used to attack his opponents while making the public think this was a real issue. In the U.S., there has been the border wall to be built against a fantasy immigration crisis. In 2020, there will be new fantasy crises which will look like real political issues to debate on the surface, but the real goal is increased power for the Wannabe King.

Elimination of Those Around Them

Like kings of old, Wannabe Kings demand loyalty but give little in return. In fact, they attack those who have helped them when they become inconvenient or unwilling to bow down fully to their power. In extreme cases, they kill off their associates, like Hitler, Stalin, and Mao did, as well as Pol Pot in Cambodia and Idi Amin in Uganda in the 1970s.

In modern times, Putin is widely believed to have disposed of some of his former associates and critics this way, and Kim Jung-Un is widely believed to have killed his half-brother. Donald Trump is well known for turning against numerous associates and cabinet appointees, dismissing them via Twitter and publicly humiliating them.

In 2020, expect a further narrowing of decision-making and schemes to a small group of like-minded associates working directly out of the Wannabe King’s office.

Lying to the Public

Wannabe Kings lie constantly and successfully. What most people don’t realize is that such chronic lying and conning is a characteristic of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), and not narcissistic personality disorder (which mostly involves exaggeration). In fact, the DSM-5 states that deceitfulness is a characteristic of ASPD and not NPD.6

While most people recognize traits of narcissism in Wannabe Kings, they usually miss the antisocial traits, which explains why they are highly aggressive risk-takers who lack remorse, may enjoy others’ pain, and are generally persuasive con artists. This dangerous combination of narcissism and antisocial behavior in leaders has also been called malignant narcissism by Erich Fromm and many others.7

In 2020, the lies of these Wannabe Kings will increase for two reasons: They are empowered by getting away with it, and they feel threatened by the limits that their nations are beginning to set on them and the questions that their followers are asking, so they lie more to support their previous lies. They will work hard to recruit an army of loyal followers to fight the ever-widening number of people who realize how dangerous and deceitful they are. They have so many secrets that more are bound to be revealed in 2020.

Conclusion

2020 will be a very interesting year for Wannabe Kings and those who want to understand them. People with personality awareness will be less surprised and more able to make wise decisions—as voters, public figures, and associates of Wannabe Kings. We will see which nations realize that “the political issue’s not the issue, the personality is the issue” and will take power away from them, rather than giving them more.