Yes, You Can Be an Ethical Tech Consumer. Here’s How.

Products that we enjoy continue to create privacy, misinformation and workplace issues. We can do better at getting the industry to do better.

Via NYTimes, By Brian X. Chen

It has never felt worse to be a technology consumer. So what can you do about it?

That’s the question of the year after many of the biggest tech companies were mired in scandal after scandal or exposed as having committed necessary evils to offer the products and services that we have so blissfully enjoyed.

Those instant Amazon deliveries? They sure are convenient, but Amazon warehouse workers in Europe protested the company during Black Friday, describing their working conditions as inhuman.

You might have considered deleting Facebook after the social network confessed that Cambridge Analytica, a political consulting firm, had improperly obtained the data of millions of users. If that didn’t convince you, maybe the security breach exposing the data of 30 million Facebook accounts did.

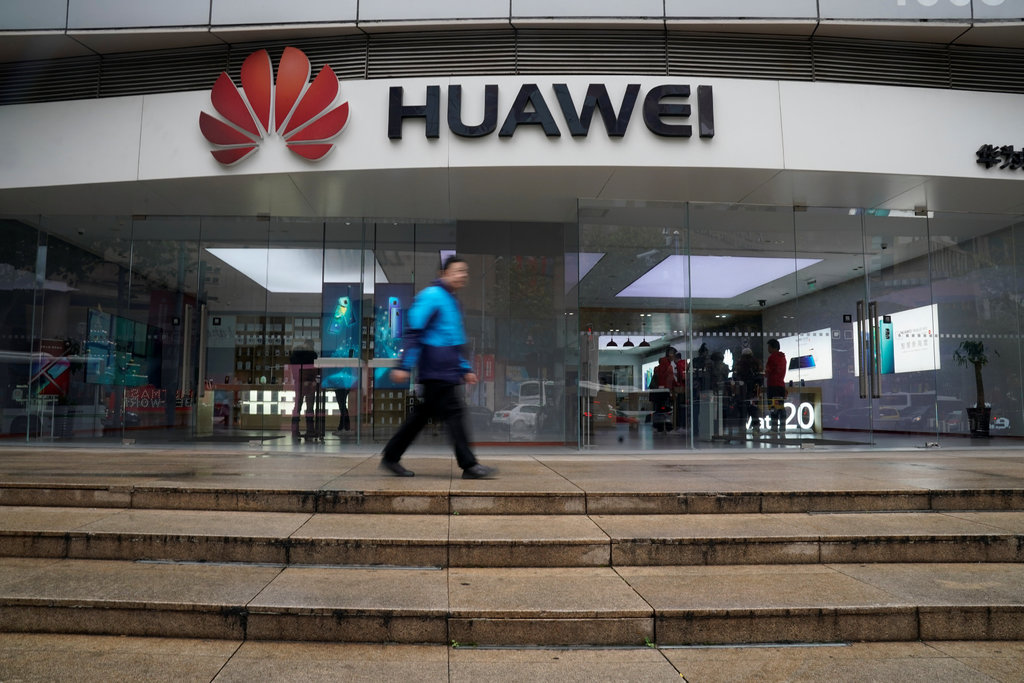

Google also came under fire, from its own employees, for working on a censored version of its search engine for China and for protecting executives who were accused of sexual misconduct.

All of this bad behavior circles back to you. We are the buyers, users and supporters of the products and services that help Big Tech thrive.

So what do we do at this point to become more ethical consumers?

“I think this is an incredibly powerful question to ask,” said Jim Steyer, chief executive of Common Sense Media, a nonprofit that focuses on technology’s impact on families. “It’s a very important moment where consumer behavior can have a transformational impact.”

I talked to a broad range of people — ethicists, activists, environmentalists and others — about how to become a more empowered, socially responsible tech consumer. Here’s what they agreed on.

Boycott and Shame

First and foremost, when tech does you wrong, one of the most powerful ways to protest is to take your business elsewhere and ask your friends and family to go along.

Last year, hundreds of thousands of customers abandoned Uber in favor of alternatives like Lyft after the ride-hailing company’s many scandals, including repeated accusations that it turned a blind eye to sexual harassment. That choice became a movement known as #DeleteUber. This year, people frustrated with Facebook took part in a #DeleteFacebook campaign.

The financial impact of these actions may not have been huge. Uber continues to grow (while still losing money) as it marches toward an initial public offering. Facebook has reported increased profits, though its user growth has slowed.

Even so, damage to a brand may have plenty of repercussions because it motivates the company to change its behavior, Mr. Steyer said. Both Uber and Facebook, facing enormous pressure, have modified some of their practices and committed to improvements.

“Sometimes shame is one of the most important arrows in your quiver,” Mr. Steyer said.

Give Up Convenience for Independence

We can also take the path less traveled — that is, take our data and money to products made by more ethical vendors.

Many people have hesitated to delete Facebook because doing so felt futile. Facebook is an all-in-one place for discovering local events, reading news, watching videos and staying connected to friends and family. The company also owns Instagram and WhatsApp, two of the largest photo-sharing and messaging services.

Pulling the plug on Facebook is a hassle, but not impossible. Taking on the challenge of finding alternatives is an example of how people can give up some convenience in exchange for individual empowerment, said Shahid Buttar, a director of grass-roots advocacy for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital rights nonprofit.

There is no direct replacement for something as convenient as Facebook. But if you go piecemeal, Mr. Buttar said, there are options. These include using an RSS reader, a software tool for getting a comprehensive feed of news sources that are self-curated; messaging people with a service like Signal, which is open-source software; and looking up events on organizing services like Meetup.

The same approach can be applied to Google if you take issue with its behavior. While Google offers a comprehensive suite of web services, including news, email and maps, you could switch to an alternative for each of those products.

Slow Down

You can do the world a favor by simply slowing down your consumption.

A chief example: When ordering from Amazon or other online retailers, think twice before you opt for same-day or overnight delivery, even if it’s free. Other than the human toll of fast service, which has included miscarriages by pregnant workers at Verizon warehouses, there is an environmental impact.

A rush shipment could involve multiple vehicles and various facilities before it gets to your door. So pause and ask yourself if you actually need that smartphone or scented candle tomorrow. If you can wait, choose no-rush delivery, which could take about a week.

You can reduce your environmental impact further by delaying how often you upgrade technology. That can be achieved by regular maintenance of devices, including smartphones, laptops and tablets.

Vincent Lai, who works for the Fixers’ Collective, a social club in New York that repairs aging devices, said people could become more empowered by repairing, maintaining and modifying products to escape the upgrade cycle that tech companies impose.

When your smartphone seems to be slowing down, for instance, take steps to speed it back up by purging some photos and apps to clear storage, replacing an aging battery or reinstalling the operating system.

“One of the things you can do to be more responsible is to take greater ownership of your stuff,” Mr. Lai said.

Think About Your Friends

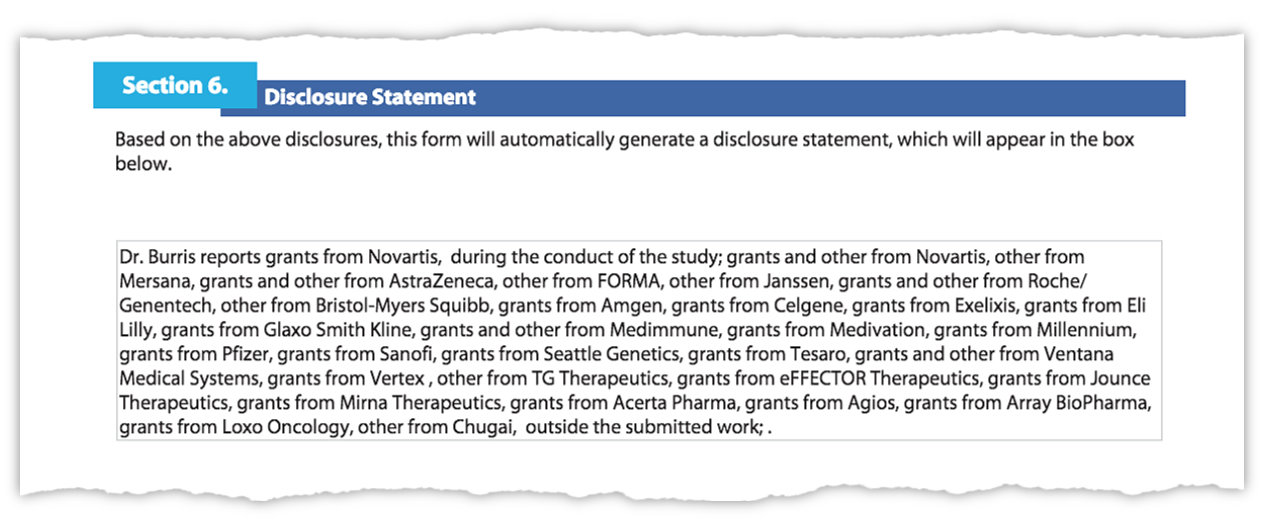

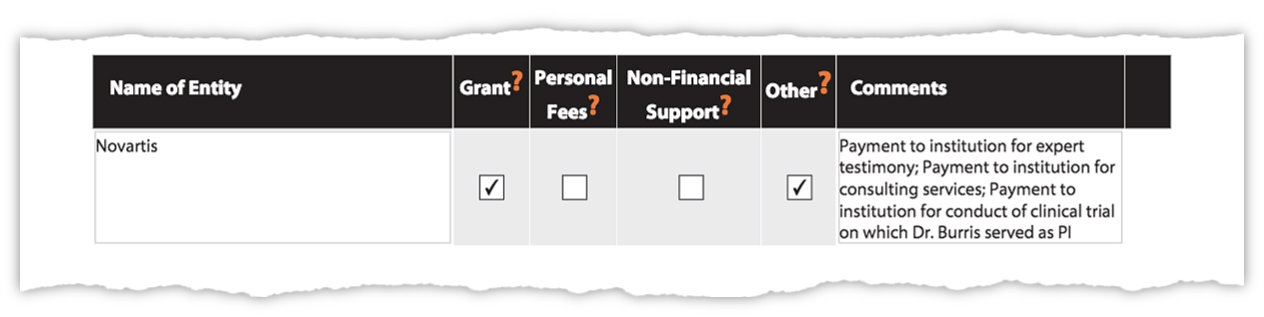

The Cambridge Analytica scandal this year illustrates our responsibility to think about others, not just ourselves, when using technology.

When Cambridge Analytica worked with a researcher who distributed a questionnaire app on Facebook to about 270,000 Americans, people who responded to the questions unwittingly shared data about their Facebook friends. As a result, the personal information of 87 million people was harvested to create voter profiles and to target political messages.

The sharing of friends’ data might have been prevented if Facebook users had been aware of their privacy settings. One now-defunct setting was called Apps Others Use, which controlled the information that your friends shared about you when they used apps, including your birthday or hometown.

In other words, if people had disabled Apps Others Use, Cambridge Analytica most likely couldn’t have collected the data of their friends. More important, if those who took the quiz were aware of the potential of sharing information about their friends, they might have opted not to participate.

But how can you be more conscious of your actions when technology is so confusing in the first place?

Education is key. Mr. Buttar said a network of 85 groups that make up the Electronic Frontier Foundation Alliance hosted workshops across the United States that taught people more about issues like digital privacy and data protection. And many online forums and publications track these issues closely.

The bottom line is that you are not alone. And if a company makes it too difficult for you and your friends to stay safe while staying connected, you can leave.

“If you’re really uncomfortable with the values of a company, don’t use their product,” Mr. Steyer said.

Read more about how to keep yourself safe and be less wasteful with technology.

Brian X. Chen is the lead consumer technology writer. He reviews products and writes Tech Fix, a column about solving tech-related problems.