I‘m on board with David Brooks here.

Maslow was a great thinker, but the pursuit of self as the highest goal, which has spawned the “me” generation, has always struck me as a cold and removed way of living. Selfish, in more pedantic terms. Especially when juxtaposed within a marriage or close romantic relationship.

Life is lonely enough when you really get down to it. Only a deep union with others, the type that is completely unattached to self focused goals, and one we embrace with no weighty fears of failure, can fight off that loneliness.

When Life Asks for Everything

The first is what you might call The Four Kinds of Happiness. The lowest kind of happiness is material pleasure, having nice food and clothing and a nice house. Then there is achievement, the pleasure we get from earned and recognized success. Third, there is generativity, the pleasure we get from giving back to others. Finally, the highest kind of happiness is moral joy, the glowing satisfaction we get when we have surrendered ourselves to some noble cause or unconditional love.

The second model is Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs. In this conception, we start out trying to satisfy our physical needs, like hunger or thirst. Once those are satisfied we move up to safety needs, economic and physical security. Once those are satisfied we can move up to belonging and love. Then when those are satisfied we can move up to self-esteem. And when that is satisfied we can move up to the pinnacle of development, self-actualization, which is experiencing autonomy and living in a way that expresses our authentic self.

The big difference between these two schemes is that The Four Kinds of Happiness moves from the self-transcendence individual to the relational and finally to the transcendent and collective. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, on the other hand, moves from the collective to the relational and, at its peak, to the individual. In one the pinnacle of human existence is in quieting and transcending the self; in the other it is liberating and actualizing the self.

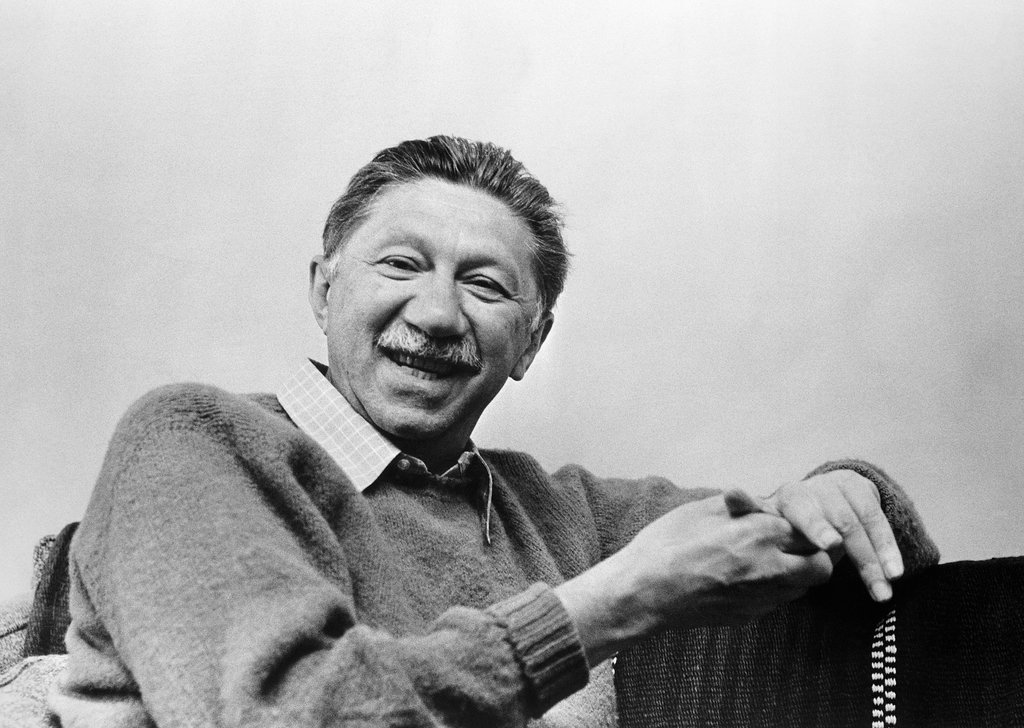

Most religions and moral systems have aimed for self-quieting and self-transcendence, figuring that the great human problem is selfishness. But around the middle of the 20th century, Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers and others aimed to liberate and enlarge the self. They brought us the self-esteem movement, humanistic psychology, and their thinking is still very influential today.

For example, on Tuesday one of America’s leading marriage researchers, Eli J. Finkel, publishes an important book called “The All-or-Nothing Marriage.” It’s quite a good book, full of interesting insights on contemporary marriage. But it conceives marriage completely within the Maslow frame.

In this conception, a marriage exists to support the individual self-actualization of each of the partners. In a marriage, the psychologist Otto Rank wrote, “one individual is helping the other to develop and grow, without infringing too much on the other’s personality.” You should choose the spouse who will help you elicit the best version of yourself. Spouses coach each other as each seeks to realize his or her most authentic self.

“Increasingly,” Finkel writes, “Americans view this definition as a crucial component of the marital relationship.”

Now I confess, this strikes me as a cold and detached conception of marriage. If you go into marriage seeking self-actualization, you will always feel frustrated because marriage, and especially parenting, will constantly be dragging you away from the goals of self.

In the Four Happiness frame, by contrast, marriage can be a school in joy. You might go into marriage in a fit of passion, but, if all works out, pretty soon you’re chopping vegetables side by side in the kitchen, chasing a naked toddler as he careens giddily down the hall after bath -time, staying up nights anxiously waiting for your absent teenager, and every once in a while looking out over a picnic table at the whole crew on some summer evening, feeling a wave of gratitude sweep over you, and experiencing a joy that is greater than anything you could feel as a “self.”

And it all happens precisely because the self melded into a single unit called the marriage. Your identity changed. The distinction between giving and receiving, altruism and selfishness faded away because in giving to the unit you are giving to a piece of yourself.

It’s not just in marriage, but in everything, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs has always pointed toward a chilly, unsatisfying version of self-fulfillment. Most people experience their deepest sense of meaning not when they have placidly met their other needs, but when they come together in crisis.

Rabbi Wolfe Kelman’s life was fraught with every insecurity when he marched with Dr. King in Selma, but, he reported: “We felt connected, in song, to the transcendental, the ineffable. We felt triumph and celebration. We felt that things change for the good and nothing is congealed forever. That was a warming, transcendental spiritual experience. Meaning and purpose and mission were beyond exact words.”

In one of his many interesting data points, Finkel reports that starting around 1995, both fathers and mothers began spending a lot more time looking after their children. Today, parents spend almost three times more hours in shared parenting than parents in 1975 did. Finkel says this is an extension of the Maslow/Rogers pursuit of self-actualization.

I’d say it’s evidence of a repudiation of it. I’d say many of today’s parents are moving away from the me-generation ethos and toward covenant, fusion and surrendering love.

None of us lives up to our ideals in marriage or anything else. But at least we can aim high. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs too easily devolves into self-absorption. It’s time to put it away.